The most famous aircraft developed during World War II were undoubted those fast and sleek fighters, or perhaps those brawny bombers. But the war years were a time of incredible technological advancement by all countries involved, and aviation itself grew more than many people today realize. For example, did you know that helicopters were developed during the Second World War? Both the Allied and Axis powers had extensive rotorcraft development projects.

Only a handful of the most successful designs survived the war and went on to be developed into the attack and transport helicopters used in the post-war world. But the experiments and risks that early pioneers took helped shape our understanding of what a rotorcraft could be—and what it could do.

One type of rotorcraft had been extensively tested and used before the war had even broken out. The autogyro, sometimes called a gyrocopter, was a typical design that all sides used throughout the war.

True helicopters as we know them today weren’t developed until later. But both the Americans and Germans had helicopters in use during the war. Igor Sikorsky, a Russian immigrant to America, spent years perfecting his designs to help his adopted home country win the war.

Related: Top 12 Korean War Helicopters | The 13 Best US Marine Corps Helicopters

Table of Contents

1. Cierva C.30A

The precursor to the modern helicopters was undoubtedly the autogyro.

An autogyro or gyrocopter is a craft that uses a rotor to generate lift. But unlike a modern helicopter, autogyros don’t apply power to the rotor blades. Instead, they rely on the aircraft’s forward motion and air passing through the blade to make them spin. They can get their forward speed from either a traditional airplane propeller or by being pulled along.

The invention of the autogyro is generally credited to Juan de la Cierva, a Spanish civil engineer. He was the first person to successfully fly a stable rotor-wing aircraft, the C.4, in 1923.

He fine-tuned his design over the years. He perfected various problems in the design, and that aircraft that met with the most acceptance was the C.30. All of the work the de la Cierva did along the way fed the knowledge that designers needed to build true helicopters.

Cierva’s autogyro designs were built all over the world under licensing agreements. For example, in Germany, Focke-Wulf built them under license and eventually designed the Fw 61. In the UK, the Cierva Autogyro Company produced many of Cierva’s designs. Licensees also included Avro in the UK, Kellett in the US, and Liore et Olivier in France.

The C.30 looked like a steam-punk mash-up of pre-World War II-era aircraft. The fuselage featured a single open cockpit, forward-mounted radial engine, and tailwheel landing gear. It looked like a biplane fuselage, but the wings were replaced by a rotor mounted above the cockpit.

Despite its slightly ungainly looks, the C.30 could fly at 110 miles per hour and had a 285-mile range. In the UK, the Royal Air Force conscripted many C.30s into service at the outbreak of World War II, but it’s unclear how or if these crafts were used in combat. Undoubtedly, its roles were limited to reconnaissance and scouting missions.

2. Focke-Wulf Fw 61

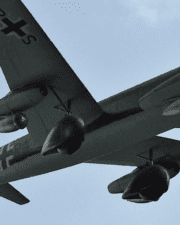

The Fw 61 was a technology demonstrator built in Germany before the beginning of WWII. It was an autogyro design, but the company would use the lessons it learned from the program to build true helicopters.

The Focke-Wulf looked and flew more like an airplane than a helicopter. It needed some forward speed to fly. It had two large rotors, each mounted outboard on open-framed struts. It had tricycle landing gear and a traditional radial engine-driven propeller on the front.

Only two Fw 61s were built, and the design first flew on July 26, 1936. The design was very much based on Cierva Model C.30 autogyros that Henrich Focke built under license during the years between the Great Wars.

3. Focke-Achgelis Fa 223 Drache “Dragon”

With the lessons that they learned from the Fw 61 gyrocopter, Fock-Wulf became Focke-Achgelis and began focusing more of their design expertise on performance and capability. The company may be best known for the Fw 190 fighter, but they worked hard to develop various rotorcraft as well.

The Fa 223 began life as the Fa 226 Hornisse, or “Hornet.” It was a six-passenger transport helicopter design that Lufthansa commissioned for commercial passenger service. However, the military became intrigued, and the Fa 223 Dragon prototypes were completed in the fall of 1939.

Unfortunately for the design, test flights were delayed for an entire year. When it did fly, in late 1940, the craft reached 113 miles per hour and got up to 23,300 feet above the ground. For those days, that was impressive for any rotorcraft.

The final Fa 223 had a teardrop-shaped fuselage that held a single large BMW engine. The engine drove two power shafts that spun two separate rotors to each side of the craft.

The look of the Fa 223 looks more like an airplane of the time than a modern helicopter. Indeed, it’s an interesting vehicle in that it personifies the bridges designers had to cross to go from one type of aircraft to an entirely new one.

The Fa 223 was just getting put into overdrive as the war spun out of Germany’s favor. Only 20 Fa 223s were built, but the company continually tinkered with the design. At one point, they even put two of the craft together to make one large four-rotor transport called the Fa 223Z “Twin.”

Several Fa 223 were used after the war in France and Czechoslovakia. They flew until around 1946.

4. Flettner Fl 282 Kolibri “Hummingbird”

Focke-Achgelis was not alone in their development of rotorcraft for Nazi Germany. During the same period, Anton Flettner was working on similar designs. He started with the single-seat Fl 265 prototype. Six were built starting in 1939.

But the resulting Fl 282 “Hummingbird” was definitely more interesting. Flettner built 24, and they were used by both the German Navy and the Luftwaffe. The Fl 265 and 282 were the first examples of a synchropter. A synchropter has two rotors mounted side by side on short strut-like wings. The rotors are mounted at an angle, and they intermesh.

The two rotors were powered by a seven-cylinder air-cooled radial engine built by Bramo. It put out 160 horsepower. The rotors were counter-rotating, meaning that the helicopter did not need a tail rotor. The intermeshing rotors also reduced the total rotor span of the aircraft, making it more useable on ships for the Navy.

Besides the unique design, the Fl 282 looked much like other rotorcraft of the period. The fuselage was mostly taken up by the engine housing. The forward end had an open-air cockpit.

The Navy used the Flettner helicopters for reconnaissance since they could be launched and landed on warships. They even made a version that could be launched from submarines! The design was popular, and at one point, the Luftwaffe had an order in for 1,000 more Fl 282s. But history had other plans, and ultimately only two dozen were ever made.

5. Sikorsky R-4 “Hoverfly”

Most of the rotorcraft from World War II have more or less become footnotes in history. Gyrocopters are still used today, but they are limited to small enthusiast groups and home-built kits. The companies that designed those German helicopters? Long gone.

But in America, a Russian immigrant from Kiev named Igor Sikorsky was polishing a design that would create the future of powered helicopters. Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation has been in business since 1923. Not only were they working on rotorcraft, but they also designed and built Pan American Airways‘ first long-distance flying boats.

Sikorski’s test platform for the helicopter was his VS-300. It made a tethered flight in 1939 and a free flight in 1940. Sikorski rolled the testing and design work from that prototype into the R-4, which eventually became the world’s first mass-produced helicopter.

The R-4 first flew in 1942 and was known as the Hoverfly. It served with the US Army Air Force, the Coast Guard, and the Navy. It also served for the UK Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm. Several variants existed over the years, and around 200 of them were built in total.

The R-4 looked much more like a modern helicopter than any of its WWII compatriots. It had an enclosed cockpit with side-by-side seating for two. It had one powered large main rotor on the top for lift and a smaller antitorque rotor on the tail.

During the war, the R-4 took over the roles for the Allies that various C.30 autogyro versions had filled. In 1945, a Canadian R-4 became the first aircraft to rescue a downed crew in the Arctic. An R-4 was also the first actual helicopter to land at sea and the first helicopter to land on a ship.

In general, however, the R-4’s capabilities were like those of the autogyros and German helicopters of the time. Its strength lay solely in its ability to take off and land vertically. It didn’t have the payload capacity or the range to operate in combat, and it carried no weapons or offensive armaments. Instead, it was used for observational purposes and as a single-person transport—usually for VIPs or the wounded.

Related Posts